Maps in Root RPG

Last Updated:

I have in general been shying away from using maps in my games.

Part of this is a general reluctance to do anything battlemapy. I don’t want my players to feel tied down to just the places that have prepared maps. I don’t want the inconsistency between encounters with maps and encounters without them. Not coincidentally, the games I gravitate towards the most are ones that assume “theater-of-the-mind” action.

Of course, one can use zoomed out maps as well. I’ve tried a few times to make rough world maps, but they’ve ended up being so low-detail that they don’t add much (“here are the mountains; this is the big city”) and are soon forgotten. Since we play on Zoom, there’s no opportunity for me to have a big piece of paper that I plop down in the middle of the table every session. Screen sharing takes away from everyone’s faces. Switching tabs is annoying.

Root: The Roleplaying Game is making me enthusiastic about maps.

Board Game Turned Roleplaying Game

Root the RPG, mostly to its advantage, has mechanisms that are heavily drawn from the Root: A Woodland Game of Might and Right board game.

One of those consistencies is that both games take place in a Woodland of 12 clearings. Each clearing is the equivalent of a town, and they’re interconnected by a network of paths, usually two or three per clearing. In the boardgame, these are the areas that players fight over to control. In the RPG, these are locations that the PCs can visit and have adventures in.

The boardgame version of Root. Image credit: Leder Games

It turns out that this is the perfect level of abstraction for a world map. 12 “towns” is enough that we probably won’t visit all of them unless the campaign goes really long, but it’s few enough that the players can recognize each one and feel familiar in the overall space.

Even better, though, is the way that the Woodland gets created. The RPG rulebook has instructions for the GM on how to generate the initial state of the world, and they’re wonderful.

In the RPG, the PCs are members of a band of vagabonds, talented and adventurous social outsiders. The Woodland itself is in the midst of a war among several factions, such as the Marquisate (cats) or the Eyrie (birds). (These, too, are drawn from the board game.)

Seeding the Map

To set up the Woodland, after either choosing a pre-made arrangement of clearings or generating one, and rolling for the clearing names and dominant species, the GM simulates the invasion of the Marquisate. Starting from one corner, they roll dice to determine what clearings get conquered. The cats need higher and higher numbers for success the farther they are away from their initial clearing and its Stronghold.

Once the GM has rolled for the Marquisate across all 12 clearings, it’s time for the Eyrie to get itself together and push back. With more dice rolls the Eyrie moves from the opposite corner across the map, taking clearings for itself and occassionally adding Roosts, which are that faction’s seats of power.

During this process control can flip, with a clearing going from Marquisate control to the Eyrie. When that happens, the GM notes that clearing as “contested.” Narratively, it’s a place of heavy fighting that has seen a lot of damage.

Mechanically, contested clearings come up when the next faction, the Woodland Alliance, is added. They rely on the sympathy of a clearing’s denizens for support, and that’s easier to get (represented by a lower target number for the dice) in places that have seen the costs of war up close.

There’s then a final set of rolls, where the denizens themselves have a very small chance of regaining control of a clearing, removing any faction that’s there.

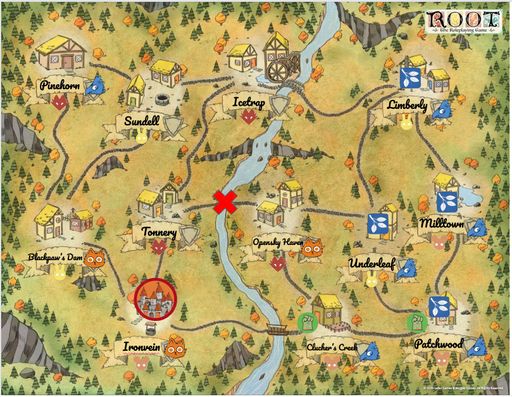

I went image searching for some icons and imported them into Google Slides so I could make this map and share it with my players. Here’s what it looks like:

Telling the Story

This process provides a map, but it also provides a story. During Session Zero I was able to describe to my players how the Marquisate initially pushed north along the western edge of the Woodand, going all the way up to Pinehorn and over to Icetrap. Then they crossed the bridge to Clutcher’s Creek and got the entire southeast corner before the Eyrie, starting from Limberly, mounted a counter offensive that retook control of almost everything east of the river.

The Eyrie also had a northern campaign that retook Icetrap and Pinehorn, but while that was happening, the Woodland Alliance took advantage of the conflicts in Clucher’s Creek and Patchwood to start spreading their message, and it caught on. Finally, the denizens made a longshot roll and kicked the Eyrie out of Icetrap and took it for themselves.

I felt like I generated a ton of flavor that makes these places unique, giving me a leg up to build on with the campaign. The “inconsistencies” in the random result were really just interesting questions that let me add even more to the story of the Woodland.

- Why did no faction ever control Tonnery or Sundell? I decided that Tonnery is heavily fortified, and they made just enough nice with the Marquisate that they weren’t worth the cost of conquering (yet). Sundell, on the other hand, is poor, with no resources left after armies went through. There’s barely anything left to govern.

- Why were the denizens able to retake Icetrap from the Eyrie? Perhaps “Icetrap” is well-named, and with winter coming on the Eyrie pulled its forces back to the southeast to fortify them there.

- How come Blackpaw’s Dam is far from the river? The names were randomly assigned. But I think there used to be a river there that’s dried up. I bet if it ever flowed again there might be disaster for the Marquisate mines in Ironvein. Is the Blackpaw family still around? Where did they go?

- Why couldn’t the Eyrie take Opensky Haven, when they had an easy time of everything else on that side of the river? Perhaps “Opensky” is a clue… no nearby trees means no cover for birds as they mobilize their troops. No trees makes it a good place for a fairground. If it’s autumn, should we be having a Harvest Festival?

Kicking Off the Campaign

Two of these locations are in obviously precarious states right at the start: Pinehorn—home to some rather fanatic Eyrie loyalists, it seems—is quite cut off from the main Eyrie government. Are they sitting ducks, ripe for the Marquisate to roll in? Or is the Marquisate too busy worrying about Opensky Haven, which is itself quite off, especially since the players used their “Daring Exploit” at the end of Session Zero to destroy the bridge between it and Tonnery.

Seeing the map, the players could tell that the Woodland was alive. This map does not describe a stable situation. They could also use it to decide where their characters were from, adding both to their characters’ backstories and enhancing the stories of these places in the process.

- Veto the echidna saw the Marquisate’s initial invasion from their family’s home outside of Ironvein.

- Dewly the mouse may have been involved in the destruction of the mill in Icetrap around the time that it changed hands.

- Scurry the Squirrel saw too much in Sundell, and lost his partner there.

- Spinach the plover lived with her noblilty parents in Clutcher’s Creek, and doesn’t mind dropping names to get her friends out of Eyrie captivity.

Now I Want More Maps

Building this map was easy, and—since I rolled the dice at least 60 times—a fun little game for me in its own right. And the result of that process has set our campaign up with clear future paths that we could take. It gave the players a sense of where their characters were from, and the places their characters could go.

We’ve already had one full session of play, where they put a stop to some thieving ruffians on the path between Opensky Haven and Underleaf. There also may be one fewer wooden-construction roadhouse in that area as well. I’m looking forward to where they choose to go next.

And, I have a mind in future games of any system to push harder on making maps at roughly this level of detail. I don’t need a street-by-street map of Halcyon City, but maybe something to show the relationship between the neighborhoods and the waterfront? (It’s not Halcyon City without a warehouse district, after all.) Enough fidelity to start providing a sense of place, but not so much that it stifles the freedom to iterate and expand at the table.